Meet James Thomas, a second year Master’s student at the Oxford University School of Geography and Environment. James is currently studying environmental policy and focusing on forest governance with a regional interest in Indonesia. He’s based not too far from our base in Central Java and by chance we bumped into each other at a local restaurant before striking up a very interesting conversation about issues surrounding the wood industry in Java. We have kept in strong contact with James, and thought we’d shoot him some questions with the idea of giving you a non biased, informative, educated and independent view of how things work here. Check out the interview below, and we want to say a big thanks James for taking the time to give such insightful information.

A Independent View

(Above Left) A Perum Perhutani forest plot in Tlogorejo, a village near Pati city. The teak here is over fifty years old and represents the highest quality in the area. The trees, cassava is planted and raised by proximate villagers who receive a wage from Perhutani.

(Above Right) This is from a Trees 4 Trees cutting. The Sengon Laut wood pictured here will go to a furniture factory in Semarang. Trees 4 Trees also helps farmers in collective bargaining with factories to ensure fair exchange.

Hi James, how are you? What’s been happening the last few days here in Central Java?

Hey Michael. I’m doing well, thanks. Let’s see, the last few days I have been between two different Kecamatan, or sub-districts, within the Pati Regency. In Gunungwunggkal I have been surveying agro-foresters with my enumerator team, and in Tlogowungu I have been commuting to the city to speak with government employees about their forest management and community outreach. Between the two kecamatan is a beautiful (though sometimes difficult to navigate) road that begins to approach Gunung Muria, the mountain that crowns northern Central Java.

So I’m just wondering if you could tell me a little bit about yourself? And what brings you here to Indonesia?

Sure thing. I’m a second year Master’s student at the Oxford University School of Geography and Environment. I study environmental policy and focus on forest governance with a regional interest in Indonesia. I lived in northern Central Java in 2010-2011, teaching English at a vocational farming school in Pati through the US State Department. While living and teaching in the village of Tlogowungu, I got to know my teachers and students who were practicing or came from families with practicing farmers, agro-foresters, and foresters. At one point a social forestry NGO showed up at SMK Farming to hold a regional meeting with many of the teachers at my school. After attending this meeting, I began to consider all the different institutional factors that manage forests and seek to provide social assistance throughout Java. The issue interested me so much that I enrolled in graduate school to study it further. So, at the moment, I’m studying forest governance in northern Central Java for my Master’s thesis. Also, I love Indonesian food, so I’m eating as much as I can in the three months I have for my fieldwork. Bring on the nasi.

How have you found the transition from the USA to Central Java? You seem to have picked up Bahasa Indonesia quite well! Has that been a challenge for you?

While my first experiences in Central Java contained instances of culture shock, it now feels great to return. I hadn’t realized how much I missed the people, the food, and the beautiful landscape of this province. As far as my Bahasa Indonesia, it gets me through my day-to-day, but it needs some polishing, to be sure. I had several weeks of language training before beginning my teaching in 2010, but most of my proficiency comes from hanging out in warungs, chatting with community members in and around forests, and trying to get a laugh or two. Operating in another language provides some significant challenges, but so many people here are willing to help me both with the language and with the logistical support of my research that none of theses challenges seem insurmountable.

(Above) Gunungwungkal, my second field-site. This pictures shows mixed usage of rural systems: tiered cassava planting gives way to teak trees in the middleground and sengon laut in the background.

If it’s ok can we talk a little more about your current activities here in Indonesia. Would you mind shedding some light on the experiences you have had here, and give our readers a little bit of information on the chain of custody involved in obtaining wood here in Indonesia?

My thesis research is focused on identifying what institutions provide assistance to small-scale foresters, what patterns exist in the paths to accessing this institutional help as measured by farmer livelihood and geographic location, and points of potential collaboration for these institutions. I consider three major players when it comes to small-scale forest assistance: the State Forest Enterprise (Perum Perhutani), the local government forestry offices (Dinas Kehutanan), and the lone action-oriented social forestry NGO operating in Central Java, Trees 4 Trees.

Timber products produced in this corner of Java are often the result of a long value-chain that can stretch from a farmer on the slopes of Gunung Muria to a consumer in New York or Sydney. My work focuses on the initial steps of this value-chain. That being said, the first two steps in the value-chain that typically results in a Javanese timber product include seeds, growers, and buyers.

The specifics are where this story gets interesting. The chain-of-custody in these first stages entirely depends on where seed comes from, and who plants/cares for them. The State Forest Enterprise (Perum Perhutani) has very formal and well-known channels for timber distribution. Community and agro-foresters utilize more informal networks to get their timber to market. And, of course, these are only the legal routes by which timber flows across the Javanese landscape.

When people talk about deforestation and the general stereotypes surrounding furniture from Indonesia, what’s your opinion on the situation since spending time in the field here? And given that info, what would you say are the major causes to these problems?

Land-use change has been occurring rapidly throughout Indonesia, most markedly during times of domestic and international political change or upheaval. This has lead to many forests being cut-down for economic, political, or cultural reasons. However, Indonesia is an unbelievably diverse country with over 14,000 islands and the worlds’ 4th largest population: patterns of land-use change on one island are not generalizable throughout the country. On Java, most of the primary forestland has been gone for a long time. While there remain many conservation areas, these conservation areas are not the people-less wilds are often depicted in narratives about deforestation. Additionally, there is an extensive history of timber production on Java, dating to before the Dutch East Indies Company. So, many of the stereotypes or dominant media narratives of illegal logging are not very applicable to timber products produced from Javanese wood.

However, illegal logging does definitely exist here. State Forests see a great deal of illegally planted and illegally harvested timber crops. The other day I was at the State Forest Enterprise office in Pati and saw two truckloads of teak that had been confiscated and were in legal disputation. It seems to me that the most sensible route to combating illegal logging on Java is to provide resources for and education about planting more trees while also ensuring positive, non-violent relationships between state foresters and proximate communities.

Are there and organizations, programs or NGOs operating in Indonesia to counter these problems? And how effective are these programs?

Focusing on Central Java, there are numerous NGOs involved in assisting with advocacy for farmers and foresters. However, I am best acquainted with the action-oriented forestry NGO, Trees4Trees. This is the only NGO I have observed in the field, and the only action-oriented social forestry NGO in Central Java that I have come across throughout over 250 farmer surveys and approximately 30 key-informant interviews. While the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) operates throughout Indonesia, it has not yet directly impacted the small-holders with whom I have surveyed.

Gauging NGO efficacy is a tricky business. What parameters do we use? Who determines those parameters? Producers? Consumers? Society? Who is society? I have seen a lot of trees going into the ground, and it seems like the bulk of these projects started from about 2006. This includes local government programs, ministry of forestry programs, Trees 4 Trees’ efforts, and a general civic enthusiasm for timber production and growing production forests. So, from the basic metric of trees planted, it seems like local government of these programs have been and continue to be effective.

How are these programs received by the local communities at the grass roots of the problems, and by the industry types associated with manufacturing furniture?

Local communities are generally receptive, though at times suspicious, of programs that provide resources. They typically apply for and receive program benefits after meeting certain qualifications, either through government channels or Trees4Trees. Thus, receiving this type of seed-aid is akin to winning a community grant, in a way.

Though I’ve had less contact with businesses, it seems that they are equally receptive and interested in receiving timber that is demonstrably legal. That is, business is widely interested in making sure that the wood they receive has a legal background for legal and ethical reasons. Further, many businesses recognize the significance of certification and the widespread, international call for certified wood products. Thus, businesses are very receptive of programs that provide timber for products that can provide consumers with guilt-free wood and also provide socio-economic benefits and fair-prices to local communities.

Where do you see the highest potential for change?

Right now, it seems that there is potential for informal networks of timber production to benefit from organizations that can ensure growers and communities make informed decisions when selling their trees. I have encountered many small-scale foresters who, when asked how they receive information on a ‘fair’ or ‘normal’ price for the timber on their land simply respond, ‘I sell for whatever price I am offered by the buyer.’ Prices on woodlots are relatively stable. What seems unstable is how much growers are receiving for their product. Trees are going into the ground, and that is wonderful. Now, it is important to continue that work by refining and reassessing programs that are already in place to provide assistance while also making sure that the full development potential of these programs is reached by providing information to growers about fair timber prices.

Given your experience internationally and here on the ground in Indonesia, what’s your take on the trees4trees program. It’s no secret that the crew here at WTP are big fans.

I think Trees4Trees offers a fascinating and local approach to promoting ethical timber production and grower livelihood. Its position as a non-profit I also feel that involving a greater diversity of institution types, business, government, NGOs, etc, helps to increase the adaptive capacity of resources and reserve management. Basically, if we have more entities that are interested in sustainable and socially conscious timber production and timber products on Java, we have a better chance of seeing this production and these products realized regardless of political, economic, or cultural shift. Trees4Trees, as an action oriented NGO, helps to assist farmers to resource and education access in this mosaic of timber production.

And so what’s next for you James? Do you see a future here in central java or do you have other plans to experience the globe a little more before settling down in one place?

As I’ve told friends here in Central Java, I absolutely love this area and hope to be able to come back for a long, long time. In several weeks, I’m heading back to England to complete my degree. I’m hoping to be selected for doctoral study so that I can continue spending time in Central Java and throughout Indonesia. I’m absolutely fascinated by this country, its beautiful land, the wonderful people that interact with it every day, and how consumers thousands of miles away push and pull Indonesian forest governance. Academically and professionally, I’m here to stay, Michael. Physically, well, we’ll see what the future holds.

Thanks for reaching out. Best of luck with everything at Walk the Plank. I think your furniture, process, and interest in social forestry is awesome!

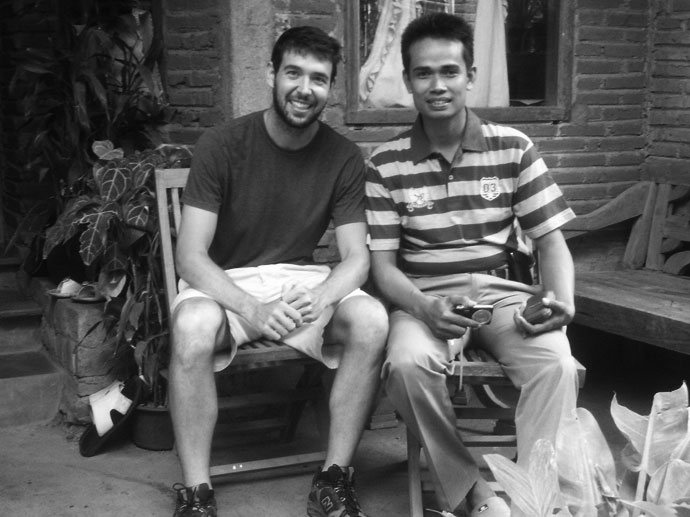

(top picture) James and good friend/colleague, Sultan, a furniture craftsman born and raised in Bugel, a village outside of Jepara.